André Malraux once wrote: “Culture is both the heritage and the noblest possession of the world.” |

Posted by Keith Tidman

What is culture? The answer is that culture is many things. ‘Culture is the sum of all forms of art, of love, and of thought’, as the French writer, André Malraux, defined the term. However, a little burrowing reveals that culture is even more than that. Culture expresses our way of life — from our heritage to our values and traditions. It defines us. It makes sense of the world.

Culture measures the quality of life that society affords us, across sundry dimensions. It’s intended, through learning, experience, and discovery, to foster development and growth. Fundamentally, culture provides the means for members of a society to relate to and empathize with one another, and thereby to form a collective memory and, as importantly, to imagine a collective future to strive for.

Those ‘means’ promote an understanding of society’s rich assembly of norms and values: both shared and individual values, which provide the grist for our standards, beliefs, behaviours, and sense of belonging. Culture affords us a guide to socialisation. Culture is a living, anthropologic enterprise, meaning a story of human development and expression over the ages, which chronicles our mores, myths, stories, and narratives. And whatever culture chooses to value — intelligence, wisdom, creativity, relationships, valour, or other — gets rewarded.

Although ideas are at the core of culture, the most-visible and equally striking underpinning is physical constructs: cityscapes, statues, museums, monuments, places of worship, seats of government, boulevards, relics, artifacts, theatres, schools, archeological collections.

This durable, physical presence in our lives is every bit as key to self-identity, self-esteem, and representation of place as are the ideas-based standards we ascribe to everyday life. In the embodiment and vibrancy of those constructs we see us; in their design and purpose, they are mirrors on our humanity: a humanity that cuts across racial, ethnic, religious, social, and other demographic groups.

The culture that lives within us consists of the many core beliefs and customs that people hold close, remaining unchanged across generations. There’s a standard, values-based thread here that the group holds in high enough esteem to resist the corrosive effects of time. The result is a societal master plan for behavioural strategies. Such threads may be based in highly prized religious, historical, or moral traditions.

Still other dogmas, however, don’t retain constancy; they become subject to critical reevaluation and negotiation, resulting in even deeply rooted ancestral practices being upended. Essentially, people contest and reassess what matters, especially as issues relate to values (abstract and concrete) and self-identity. The resulting changes in traditions and habits stem from discovery and learning, and take place either in sudden lurches or as part of a gentle progression. Either way, adaptation to this change is important to survival.

This inevitability and unpredictability of cultural change are underscored by the powerful influences of globalisation. Many factors combine to push global change: those that are economic, such as trade and business; those that are geopolitical, such as pacts and security and human rights; and those that accelerate change in technology, travel, and communications. These influences across porous national contours do not threaten cultural sameness per se, which is an occasional refrain, but do quicken the need for societies to adjust.

As part of this global dynamic, culture’s instinct is to stabilise and routinise people’s lives, which reassures. Opinions, loyalties, apprehensions, ambitions, relationships, creeds, sense of self in time and place, and forms of idolatry become tested in the face of time, but they also comfort the mind. These amount to the collective social capital: the bedrock of what can rightly be called a community.

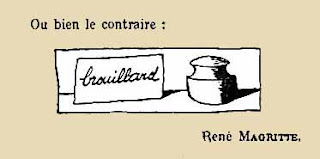

Language, too, is peculiarly adaptive to culture, a tool for varied expression: the reassuring yet unremarkable (everyday); the soaring and imaginative (creatively artistic); and the rigorously, demandingly precise (scientific and philosophic). In these regards, language is simultaneously adaptive to culture and adaptive of culture: a crucible on which the structure and usage of language remain pliant, to serve society’s bidding.

Accordingly, language is basic to framing our staple beliefs, values, and rituals — much of what matters to us, and helps to explain how culture enriches life. What we eat, what we wear, whom we marry, what music we listen to, what plays we attend, what locations we travel to, what we find humorous, what recreation we enjoy, what commemorations we observe — these and other ordinary lived experiences are the building blocks of cultural diversification.

Culture allows society to define its nature and ultimately prolong its wellbeing. Culture fills in the details of a larger shared reality about the world. We revere the multifaceted features of culture, all the while recognising that we must be prepared to reimagine and reform culture with the passage of time, as conditions shift.

This evolutionary process brings vigour. To this extent, culture serves as the lifeblood of society.