|

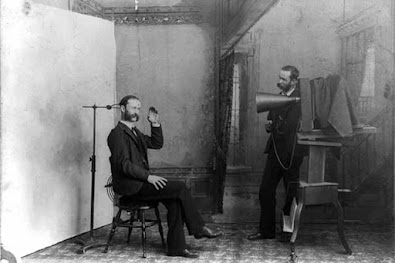

| Detail from the cover illustration for the book Rethinking Thinking |

By Martin Cohen

I’ve been thinking lot about thinking a lot! Here’s some of my thoughts…

Rule Number One in thinking, via the classic text The Art of War, is don’t do things the clever way, nor even the smart way: do them the easy way. Because it doesn’t matter what you’re wondering about, or researching or doing - someone else has probably solved the problem for you already. Flip to the back of the book, find the answer. In fact, the great thing about the ancient Chinese book, The Art of War, is that it is not a brainy book at all. It is really just unvarnished advice expressed in what was then the plainest language. We need more of that. Thinking Skill Two is to avoid ‘black and white’ thinking, binary distinctions, ‘yes/no’ language and questions, and instead interact with people in a non-linear, less ‘directive’ manner. Take the tip from ‘design thinking’ that approaches rooted in notions of questions and answers are themselves limiting insight, because questions and answers are like a series of straight lines, when what is needed is shading, colours and, well, ‘pictures’. This is why it is sometimes better to go for narratives – which are conceptually more like shapes.

Tip Number Three, which, yes, is connected to the previous tips, and that’s a good thing too, is to look for the pattern in the data. (That’s what Google does, of course, and it hasn’t done them any harm.) More generally, as I say in chapter three, these days, scientists and psychologists say that humans beings are, fundamentally, pattern seekers. Every aspect of the world arrives via the senses as an undifferentiated mass of data, yet we are usually unaware of this as it is presented to our minds in organized form following an automated and wholly unconscious process of pattern solving. However, there’s a caution that has to come with advice to pattern match, because as we become attentive to some characteristics, we start to latch onto confirmatory evidence, and may neglect - maybe indeed suppress - other information that doesn’t fit our preconceptions. Put another way, patterns are powerful tools for making sense of the world (or other people), but they aren’t actually the world – which may be more subtle and complex than we imagine.

Thinking Skill Number Four, coming in quite a different direction, is ‘pump up the intuition’. Instead of thinking about ‘what is’, think about what might be. The ability to create imaginary worlds in our heads is perhaps our most extraordinary mental tool –yet so often neglected in the pursuit of mere observations and measurements. The ability, that is, as I explore in chapter four, to take any set of facts and play with them, to consider alternatives and hypotheticals. Being ‘playful’ is what the approach is all about, and something that probably the techniques’s greatest exponent – Einstein – stressed too.

My Tip Number Five actually looks more of a caution than a counsel: put all your cozy assumptions to one side and instead be ready to rigorously test and challenge every aspect of them. This is part of the solution to the age-old problem of 'thinking you know’, when, in fact, you don’t, which has been the task of philosophy ever since Socrates walked the streets of Ancient Athens challenging the arrogant young men to debate. 'Thinking you know everything' about an issue is invariably intermingled with the tendency to only see what you expect to see, likely because you have got caught up in a particular story. Exploring some of the stories that make up the amazing tale of the moon shows how this, ‘engineering’ approach, an approach we wrongly dismiss as rather dull, actually has enormous creative power. Socrates understood that: demolishing old certainties is not an end in itself, but a precursor to allowing new ideas.

Problem Solving Strategy Number Six, my favourite tip, is to doodle! Doodles, it turns out, are another kind of ‘intuition pumps’ (like thought experiments) and that gives you the clue as to what is valuable about doodling. It is emphatically NOT about the visuals – yes some people can draw beautiful doodles, many people to curious ones, and some of us do downright awful ones – but the value of doodling lies in the freedom it gives your subconscious mind - with apologies to all those specialists in psychology who will insist on some technical definition of the term. Ideas, as the Japanese designer Oki Sato says, start small - and can easily wither at the first critical assessment.

Doodling can be metaphorically compared to watering a thousand seeds scattered into a plant tray. You don't know at the outset which of the tiny seeds will be important - and you don't care. Instead, you give them all a chance to grow a little. Doodling, we might say, is similarly non-judgmental, and, at the same time, actively in praise of the importance of small thoughts. Of course, we do this all the time here at Philosophical Investigations!

Strategy Number Seven is about a very different kind of thinking. It's all about finding the explanatory key to make sense of complexity - the kid of complexity that is all around us at every level. Here, the thinking tools you need are an eye for detail along with an ability to see broader relationships. Put that way, it seems to require rather exceptional abilities But the thinking tool here is to stop trying to work out, and maybe even control a complex system from above. That's the conventional approach – where you gather all the information and then organise it.

No, the tip here is let the complexity organise itself - and you just concentrate on spotting the tell-tale signs of order. Watch for the 'emergent properties' that arise as a system organises itself and devote yourself to preserving the conditions in which the best solutions evolve. Put another way, if the cat wants food, it will keep pestering you. Be aware of the patterns in the data!

Tip Number Eight, is the computer programmer's cautionary motto: ‘Garbage In, Garbage Out’. To illustrate this idea in the book, I looked at the science governing responses to the corona virus, which was indeed heavily driven not by real-world data, but by computer models. But forget that distinction for a moment, the point is really a very general one. In everything we do, be aware of the quality of the information you are acting on. It could be compared to decorating a room: before you apply the colorful paints, before you lay the expensive carpet, have you prepared the surfaces? Mended the floorboards? Because shortcuts in preparation carry disastrous costs down the line. It's the same thing with arguments and reasoning. That dodgy assumption you made in haste, or perhaps because checking seemed time-consuming (or just boring) to do – can easily undermine your entire strategy, causing it to fall apart like at the first brush with reality. Just as an elegant carpet is no use if the floorboard is creaking.

Thinking Strategy Nine, my last one here and the one ever so slightly paradoxically closing my book, is to use ‘emergent thinking’, by which I mean adopting strategies in life that involve exploring all the possibilities and then generating new ideas, concepts and solutions from out of combinations of those ideas which likely could not be found in them individually. Yes, the strategy sounds terribly simple, but that first stage - of exploring possibilities - can be terribly time consuming and literally, impractical. So there are a host of micro-strategies needed too, like learning how to find information quickly, and above all how to select just the useful stuff. This is why I call this strategy ‘thinking like a search engine’ in the book, but, as I explain there, search engines actually rely to a large extent on human judgements: about information relevance and quality.

You can't get away from it: sorting the garbage requires a little bit of skill along with the apparently trivial, routine procedures. Thinking requires a brain - whatever some researchers on mushrooms may tell you…