Representing reality*

By Martin CohenWhat is the relationship of words and paintings to mental representations - and 'reality' itself? The surrealist artist, René Magritte, is a philosophical favorite (along with Escher whose line drawings depict impossible staircases and infinite spirals) because so many of his pictures play with philosophical themes. Yet, less well appreciated, is his painting rests on a substantial theoretical base and a consistent personal effort to address the key philosophical question - through art - of the relationship of language, thought and reality.

In the

Second Surrealist Manifesto, René Magritte offers 18 sketches, each illustrating a supposed 3-way relationship with words and 'reality. This page explores each image in turn.

Unlike other artists of the Surrealist school, Magritte's style is highly realistic - but this is only a meant to later undermine the authority and certainty of 'appearance' - of our knowledge of the external world. As Magritte puts it:

"We see the world as being outside ourselves, although it is only a mental representation of it that we experience inside ourselves." [1]

Les Mots et Les ImagesAn object is not so attached to its name that one cannot find for it another one which is more suitable [2] The handwritten words 'le canon' is usually just translated as 'the gun' -but could this in itself be a play on the sense of 'the canon', the 'thing setting the standard', especially of beauty?

There are objects which can do without a name.

The French word for the rowing boat is '

canot' - but the play on words...?

A word sometimes serves only to designate itself.

'

Ciel' is sky... but?

An object encounters its image, and objects encounters its name. It happens that the image and the name of this object encounter each other.

As opposed to the later cases,

Sometimes the name of an object occupies the place of an image.

A hand, a box and a rock?

A word can take the place of an object in reality.

The dame is saying 'sunshine'. Or 'the sun' if you like. Does it link to the next image?

An image can take the place of a word in a sentence. [3]

Well, yes, but logically the sun should be hidden, no?

An object can suggest that there are other objects behind it.

The wall does not make me think there is anything behind it. The sun? The dame?

Everything tends to make us think that there is little relationship between an object and that which represents it. [4] Confusingly, the 'real' and the 'image' are of course the same here...

The words which serve to indicate two different objects do not show what may divide these objects from one another.

The 'surreal' labelling in French translates as 'person with memory loss' and 'woman's body'.

In a painting the words are of the same substance as the images.

But are they?

You can perceive words and images differently in a painting.

Is Magritte saying a new meaning can be created by juxtapositions like this?

A shape can replace the image of an object for any reson.

A very confusing play on shapes here...

An object never serves the same purpose as either its name or its image does.

The man is calling his horse - or is he calling his horse 'horse'?

Sometimes the visible shapes of objects, in real life, form a mosaic

René seems to have drifted somewhat from his original theme here...

Vague or unclear shapes have a precise significance every bit as necessary as that of perfect shapes.

Again,

the example has left language slightly out of the debate. But the point could be extended...

Sometimes, the names written in a picture designate precise things, while the images are vague.

Well... yes...

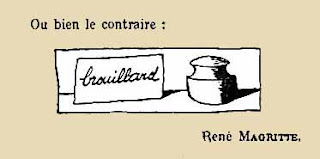

Or equally, the opposite:

But is the word 'fog' (

brouillard) itself imprecise?

Decoding Magritte The images above all appeared in an article by Magritte entitled, rather literally,

'Les mots et les images' (Words and Images), in

La Révolution surréaliste in December 1927. The series is intended to introduce the theme of all Magritte's painting, namely that of the ambiguity of the connections between real objects, their image and their name. The fifth statement here: "sometimes the name of an object stands for an image" he went on to illustrate with this image:

This is one of a series of 'alphabet paintings' or 'word paintings' produced by Magritte during his time in Paris from 1927 to 1930. Here, the words 'foliage', 'horse', 'mirror', 'convoy', written on the canvas, replace the image they designate. 'Placed at the tip of the points of a mysterious star and each inscribed on a brown stain, "any form whatsoever that can replace the image of an object", these words play a full part in the spatial composition of a new fantasy image. This painting undoes the connection that we spontaneously establish between objects, images and words.' [5]

Another clue as to Magritte's philosophy is provided by a series of paintings dealing with the concept of 'categories'. In

The Palace of Curtains (1929) two frames contain respectively the word

ciel ('sky') and a pictorial representation of a blue 'sky'. Magritte's point is that both the word and image 'represent' the 'real thing' - one works by resemblance while the other is only by an intellectual - arbitary - association.

Les Mots et Les ImagesIn two pictures called

Empty Mask (a 'mask' being a 'frame', here) Magritte again makes a point about what 'represents' what. In the first picture the frame is empty by virtue of nothing being painted in the spaces, but equally in the second frame, full of characteristic Magritte images, the frame is still empty because these fragments do not represent anything. Or so at least art historians theorise. [6]

'The dividedness, the fragmented quality and the separateness of their components deprive them of anything that resembles reality, destroys all narrative content' (says one, Bart Ottinger).

Another image,

The Threshold of Liberty (1929), adds a gun, threatening in surrealist fashion to destroy the conventional representations.

In the

Key to Dreams series, which this page starts with an image of, Magritte uses images in the style of a schoolroom reading text, probably based on the Petit Larousse, texts in which an obvious and exact correspondence is implied. Thus his simple images pack a subversive message.

It is, as one art critic says, a school reading primer gone wrong - yet sometimes, not completely wrong, for example in the image opposite (Key to Dreams,1930) the lower right-hand cell is correct.

In the six panel image above, none of the nouns (the acacia, moon, snow, ceiling, storm, desert) match up.

The title,

'Key to Dreams' (

La clef des songes) however implies that there may be deeper, hidden connections.

So are we any nearer to decoding that meaning? Not really. However, Michel Foucault knew Magritte and discussed these ideas in an essay

'Ceci n'est pas une pipe' (This is not a Pipe). Foucault has some definite suggestions on the matter.

*This essay originally appeared on the now disappeared Pi Alpha. It has been slightly updated here.Notes

• 1 This much quoted line comes from a lecture Magritte gave, entitled, 'La Ligne de vie' - how should we translate that though?• 2 The first 12 translations are based on that at http://www.kraskland.com/• 3 This is NOT the translation at http://www.kraskland.com/ - which uses 'propositon' - ridiculous!• 4 This is slightly better than the translation at http://www.kraskland.com/• 5 As explained here: http://www.centrepompidou.fr/education/ressources/ENS-surrealistart-EN/ENS-surrealistart-EN.htm• 6 For example, this interestingand informative essay here: http://courses.washington.edu/hypertxt/cgi-bin/book/wordsinimages/magritte.html