|

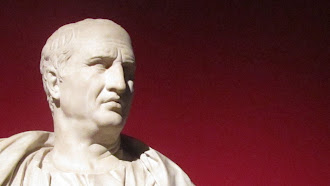

| The Roman philosopher, Cicero. In his book, De Legibus, he suggests laws should be dawn from ‘the profoundest philosophy’. |

Posted by Keith Tidman

Laws tend to accrete, one upon another. Yet, doesn’t this buildup of laws paradoxically undermine the ‘rule of law’? Wasn’t Montesquieu right to say that ‘useless laws weaken the necessary laws’, and by extension today enfeeble the rule of law?

The rule of law holds that every person and institution is equally accountable to the law. It is society’s safeguard against disorder. This presupposes that laws, in promoting the individual good, also promote the common good. The elixir to cure the ailments of society is often seen as dwelling in zealous lawmaking and rulemaking, which ironically may create even worse fissures within the rule of law itself and within the resulting social order. However mistaken such belief in the tonic may be, this regularly seems to be the guiding ideal and aspiration.

Yet, aspirations aside, the reality is that the proliferation of laws and regulations leads to redundancy, confusion, contradiction, and irrelevance among the laws that accrue over time. These factors fog up the lens through which people view laws as either just or unjust. In turn, citizens typically remain unaware of their actual liability to these amassed laws, and as a practical matter enjoy little understanding of how laws might be enforced.

Compounding the byzantine body of laws and regulations is the politicisation of their application. Governments of different political ideological leanings may well shift, especially as regimes shift, affecting the interpretation of laws. Laws being, as Thomas Hobbes wrote in Leviathan, ‘not counsel, but command’. Governments might make arbitrary decisions as to how to enforce the laws and regulations, and against whom. Political partisanship and the hazard of overcriminalisation can be the not-uncommon consequence.

When Winston Churchill warned, ‘If you have ten thousand regulations, you destroy all respect for the law’, to some people the cautionary note may have seemed an exaggeration, offered for effect. Now, many countries creak under an evermore bloated number of complex, cumbersome laws and regulations, with rule-of-law significances.

A core supposition of law is that citizens freely choose from among alternative behaviours in the daily conduct of their lives. Whether people really do have such uninhibited decision-making and choice, laws make sense, from the practical standpoint of society holding individuals accountable, only if the operative supposition of government and the community is that people deliberate and act through self-direction.

Laws and regulations ought to mirror society’s shared values, norms, conventions, practices, and customs, in order for justice to emerge. However, despite the influence of social values on laws, ‘legal’ and ‘illegal’ are not necessarily equivalent to ‘moral’ and ‘immoral’; principles of legality and morality may be only obliquely correlated.

Meanwhile, it’s precisely because of the influence of social values that laws ought to remain malleable going into the future, as core needs of the community become reimagined and reframed with time. The inevitability of novel circumstances in the future requires pliability in human thinking, and thus in law.

If laws and regulations are allowed to calcify, they shed relevance in longer-term service of the community. They no longer foster the welfare of the people, which along with social order is foundational to laws’ existence. ‘The welfare of the people is the ultimate law’, Cicero presciently observed. Outdated laws and regulations ought to be purged, barring new laws from heaping upon the crustaceous remnants of old laws. Preserving the best about rule-of-law principles requires housecleaning.

Everyday citizens often perceive the law as an impenetrably dense mass, understood and plied by a priesthood of specialists who accommodate select interests. Laws’ unfortunate opaqueness propagates ‘ignorance of the law’, despite this go-to plea not being a legally valid excuse.

The risk is that society tilts increasingly toward unequal justice, much to the disadvantage of the poor, racial and ethnic minorities, and other alienated, underrepresented subgroups less equipped to self-endorse, or to accrue and deploy power and influence to their advantage. Vulnerability and punishment and discretion are frequently proportional to financial means, in plutocratic fashion. And the rule of law, meanwhile, loses its glint.

And so, in advising that ‘A state is better governed with few laws, and those laws strictly observed’, in light of his time in history René Descartes seems commonsensical. Yet, ever since, many countries have jettisoned this simple prescription.

The profusion of laws compacting outdated and useless laws cannot continue indefinitely, without risking an irreparable stress point for jurisprudence’s workability and integrity. A moratorium on disgorging new laws, however, is insufficient alone. It is vital to clear the overgrown brush that threatens to choke the consistency, intelligibility, reasonableness, and applicability of what we want to restore by way of the rule of law and sensible jurisprudence.

That’s an achievable undertaking. The prospect of our returning to first principles regarding the rule of law as a credible and viable doctrine, beyond a muffled slogan, makes the enterprise of clearing the thicket of laws worthwhile if we want a just society.