|

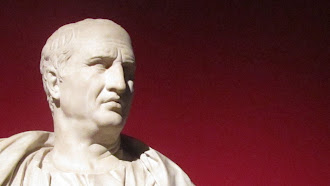

| A Barber-surgeon practising blood-letting |

Posted by Keith Tidman Is health care a universal moral right — an irrefutably fundamental ‘good’ within society — that all nations ought to provide as faithfully and practically as they can? Is it a right in that all human beings, worldwide, are entitled to share in as a matter of justice, fairness, dignity, and goodness?

To be clear, no one can claim a right to health as such. As a practical matter, it is an unachievable goal — but there is a perceived right to healthcare. Where health and healthcare intersect — that is, where both are foundational to society — is in the realisation that people have a need for both. Among the distinctions, ‘health’ is a result of sundry determinants, access to adequate healthcare being just one. Other determinants comprise behaviours (such as smoking, drug use, and alcohol abuse), access to nutritious and sufficient food and potable water, absence or prevalence of violence or oppression, and rates of criminal activity, among others. And to be sure, people will continue to suffer from health disorders, despite all the best of intentions by science and medicine. ‘Healthcare’, on the other hand, is something society can and does make choices about, largely as a matter of policymaking and access to resources.

The United Nations, in Article 25 of its ‘Universal Declaration of Human Rights’, provides a framework for theories of healthcare’s essential nature:

“Everyone has the right to a standard of living adequate for the health and well-being of himself and of his family, including . . . medical care and necessary social services, and the right to security in the event of . . . sickness . . . in circumstances beyond his [or her] control.”

The challenge is whether and how nations live up to that well-intentioned declaration, in the spirit of protecting the vulnerable.

At a fundamental level, healthcare ethics comprises values — judgments as to what’s right and wrong, including obligations toward the welfare of other human beings. Rights and obligations are routinely woven into the deliberations of policymakers around the world. In practice, a key challenge in ensuring just practices — and figuring out how to divvy up finite (sometimes sorely constrained) material resources and economic benefits — is how society weighs the relative value of competing demands. Those jostling demands are many and familiar: education, industrial advancement, economic growth, agricultural development, security, equality of prosperity, housing, civil peace, environmental conditions — and all the rest of the demands on resources that societies grapple with in order to prioritise spending.

These competing needs are where similar constraints and inequalities of access persist across socioeconomic demographics and groups within and across nations. Some of these needs, besides being important in their own right, also determine — even if sometimes only obliquely — to health and healthcare. Their interconnectedness and interdependence are folded into what one might label ‘entitlements’, aimed at the wellbeing of individuals and whole populations alike. They are eminently relatable, as well as part and parcel of the overarching issue of social fairness and justice.

The current vexed debate over healthcare provision within the United States among policymakers, academics, pundits, the news media, other stakeholders (such as business executives), and the public at large is just one example of how those competing needs collide. It is also evidence of how the nuts and bolts of healthcare policy rapidly become entangled in the frenzy of opposing dogmas.

On the level of ideology, the healthcare debate is a well-trodden one: how much of the solution to the availability and funding of healthcare services should rest with the public sector, including government programming, mandating, regulation, and spending; and how much (with a nod to the laissez-faire philosophy of Adam Smith in support of free markets) should rest with the private sector, incluidng businesses such as insurance companies, hospitals, and doctors? Yet often missing in all this urgency and the decisions about how to ration healthcare is that the money being spent has not resulted in best health outcomes, based on comparison of certain health metrics with select other countries.

Sparring over public-sector versus private-sector solutions to social issues — as well as over states’ rights versus federalism among the constitutionally enumerated powers — has marked American politics for generations. Healthcare has been no exception. And even in a wealthy nation like the United States, challenges in cobbling together healthcare policy have drilled down into a series of consequential factors. They include whether to exclude specified ailments from coverage, whether preexisting conditions get carved out of (affordable) insured coverage, whether to impose annual or lifetime limits on protections, how much of the nation's gross domestic product to consign to healthcare, and how many tens of millions of people might remain without healthcare or be ominously underinsured, among more — precariously resting on arbitrary decisions. True reform might require starting with a blank slate, then cherry-picking from among other countries’ models of healthcare policy, based on their lessons learned as to what did and did not work over many years. Ideas as to America’s national healthcare are still on the anvil, being hammered by Congress and others into final policy.

Amid all this policy ‘sausage making’, there’s the political sleight-of-hand rhetoric that misdirects by acts of either commission or omission within debates. Yet, do the uninsured still have a moral right to affordable healthcare? Do the underinsured still have a moral right to healthcare? Do people with preexisting conditions still have a moral right to healthcare? Do people who are older, but who do not yet qualify for age-related Medicare protections, have a moral right to healthcare? Absolutely, on all counts. The moral right to healthcare — within society’s financial means — is universal, irreducible, non-dilutable; that is, no authority may discount or deny the moral right of people to at least basic healthcare provision. Within that philosophical context of morally rightful access to healthcare, the bucket of healthcare services provided will understandably vary wildly, from one country to another, pragmatically contingent on how wealthy or poor a country is.

Of course, the needs, perceptions, priorities — and solutions — surrounding the matter of healthcare differ quite dramatically among countries. And to be clear, there’s no imperative that the provision of effective, efficient, fair healthcare services hinge on liberally democratic, Enlightenment-inspired forms of government. Apart from these or other styles of governance, there’s more fundamentally no alternative to local sovereignty in shaping policy. Consider another example of healthcare policy: the distinctly different countries of sub-Saharan Africa pose an interesting case. The value of available and robust healthcare systems is as readily recognized in this part of the world as elsewhere. However, there has been a broadly articulated belief that the healthcare provided is of poor quality. Also, healthcare is considered less important among competing national priorities — such as jobs, agriculture, poverty, corruption, and conflict, among others. Yet, surely the right to healthcare is no less essential to these many populations.

Everything is finite, of course, and healthcare resources are no exception. The provision of healthcare is subject to zero-sum budgeting: the availability of funds for healthcare must compete with the tug of providing other services — from education to defence, from housing to environmental protections, from commerce to energy, from agriculture to transportation. This reality complicates the role of government in its trying to be socially fair and responsive. Yet, it remains incumbent on governments to forge the best healthcare system that circumstances allow. Accordingly, limited resources compel nations to take a fair, rational, nondiscriminatory approach to prioritising who gets what by way of healthcare services, which medical disorders to target at the time of allocation, and how society should reasonably be expected to shoulder the burden of service delivery and costs.

As long ago as the 17th century, René Descartes declared that:

‘... the conservation of health . . . is without doubt the primary good and the foundation of all other goods of this life’.

However, how much societies spend, and how they decide who gets what share of the available healthcare capital, are questions that continue to divide. The endgame may be summed up, to follow in the spirit of the 18th-century English philosopher Jeremy Bentham, as ‘the greatest happiness for the greatest number [of people]’ for the greatest return on investment of public and private funds dedicated to healthcare. How successfully public and private institutions — in their thinking about resources, distribution, priorities, and obligations — mobilise and agitate for greater commitment comes with implied decisions, moral and practical, about good health to be maintained or restored, lives to be saved, and general wellbeing to be sustained.

Policymakers, in channeling their nations’ integrity and conscience, are pulled in different directions by competing social imperatives. At a macro level, depending on the country, these may include different mixes of crises of the moment, political and social disorder, the shifting sands of declared ideological purity, challenges to social orthodoxy, or attention to simply satiating raw urges for influence (chasing power). In that brew of prioritisation and conflict, policymakers may struggle in coming to grips with what’s ‘too many’ or ‘too few’ resources to devote to healthcare rather than other services and perceived commitments. Decisions must take into account that healthcare is multidimensional: a social, political, economics, humanities, and ethics matter holistically rolled into one. Therefore, some models for providing healthcare turn out to be more responsible, responsive, and accountable than others. These concerns make it all the more vital for governments, institutions, philanthropic organizations, and businesses to collaborate in policymaking, public outreach, program implementation, gauging of outcomes, and decisions about change going forward.

A line is thus often drawn between healthcare needs and other national needs — with the tensions of altruism and self-interest opposed. The distinctions between decisions and actions deemed altruistic and those deemed self-interested are blurred since they must hinge on motives, which are not always transparent. In some cases, actions taken to provide healthcare nationally serve both purposes — for example, what might improve healthcare, and in turn health, on one front (continent, nation, local community) may well keep certain health disorders from another front.

The ground-level aspiration is to maintain people’s health, treat the ill, and crucially, not financially burden families, because what’s not affordable to families in effect doesn’t really exist. That nobly said, there will always be tiered access to healthcare — steered by the emptiness or fullness of coffers, political clout, effectiveness of advocacy, sense of urgency, disease burden, and beneficiaries. Tiered access prompts questions about justice, standards, and equity in healthcare’s administration — as well as about government discretion and compassion. Matters of fairness and equity are more abstract, speculative metrics than are actual healthcare outcomes with respect to a population’s wellbeing, yet the two are inseperable.

Some three centuries after Descartes’ proclamation in favour of health as ‘the primary good’, the United Nations issued to the world the ‘International Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights’ and thereby placing its

imprimatur on ‘the right of everyone to the enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health’. The world has made headway, where many nations have instituted intricate, encompassing healthcare systems for their own populations, while also collaborating with the governments and local communities of financially stressed nations to undergird treatments through financial aid, program design and implementation, resource distribution, teaching of indigenous populations (and local service providers), setting up of healthcare facilities, provision of preventions and cures, follow-up as to program efficacy, and accountability of responsible parties.

In short, the overarching aim is to convert ethical axioms into practical, implementable social policies and programs.