03 April 2022

Picture Post #73 The Children's Hospital in Ukraine

27 March 2022

Toute Médaille a Son Revers

by Allister John Marran

The way we form our ideas, and with that, take our place in the human family, is through critical debate—which is, to consider arguments both for and against our own point of view.

The French have a saying, ‘Toute médaille a son revers.’ Every medal has its reverse. Yet all too often, the reverse side is blank. Like the medal, there are many intellectual and educational pursuits in life which, in fact, merely give us the illusion of critical debate.

It is not a form of critical debate to watch a YouTube content creator or network news show host talk about a topic, be it political or social or philosophical. It's a style of performative art which plays to a predefined audience to increase viewership or likes. Counter-intuitively, even university classes have served such purpose.

In the vacuum of a sterile single point studio there is no counter point, there is no objectivity. It's simply designed to tell an audience that already believes something that they are right. It serves as an echo chamber to bolster one’s preconceptions.

If one relies on this alone to form a holistic world view, to inform one’s opinions and to guide one’s sensibilities, one will be left far short as a person. One wouldn’t think of walking into a bank expecting to be told about the strengths of another bank. One wouldn't attend a Catholic Church wanting to find out about the teachings of the Buddha.

We are never sold the product we need. We are sold the product that the seller has in stock, or else they lose the sale. It is Business 101.

Why then do people tune in to biased news networks or YouTube shows, even enroll for classes, expecting to get factual and unbiased information? In reality, information itself has no bias. It's the slant of the deliverer, or the recipient, who through accent or omission or misrepresentation allows it to carry a biased weight and a crooked message.

20 March 2022

Would You Plug Into Nozick’s ‘Experience Machine’?

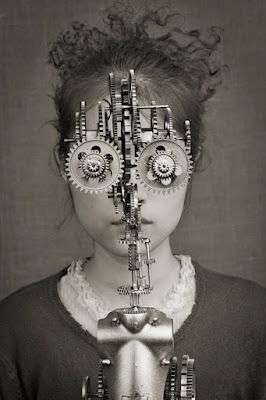

|

| Clockwork Eyes by Michael Ryan |

By Keith Tidman

Life may have emotionally whipsawed you. Maybe to the extent that you begin to imagine how life’s experiences might somehow be ‘better’. And then you hear about a machine that ensures you experience only pleasure, and no pain. What not to like!

It was the American philosopher Robert Nozick who, in 1974, hypothesised a way to fill in the blanks of our imaginings of a happier, more fulfilled life by creating his classic Experience Machine thought experiment.

According to this, we can choose to be hooked up to such a machine that ensures we experience only pleasure, and eliminates pain. Over the intervening years, Nozick offered different versions of the scenario, as did other writers, but here’s one that will serve our purposes:

‘Imagine a machine that could give you any experience (or sequence of experiences) you might desire. When connected to this experience machine [floating in a tank, with electrodes attached to your brain], you can have the experience of writing a great poem or bringing about world peace or loving someone and being loved in return. You can experience the felt pleasures of these things. . . . While in the tank you won’t know that you’re there; you’ll think it’s all actually happening’.

At which point, Nozick went on to ask the key question. If given such a choice, would you plug into the machine for the rest of your life?

Maybe if we assume that our view of the greatest intrinsic good is a state of general wellbeing, referred to as welfarism, then on utilitarian grounds it might make sense to plug into the machine. But this theory might itself be a naïve, incomplete summary of what we value — what deeply matters to us in living out our lives — and the totality of the upside and downside consequences of our desires, choices, and actions.

Our pursuit of wellbeing notwithstanding, Nozick expects most of us would rebuff his invitation and by extension rebuff ethical hedonism, with its origins reaching back millennia. Our opting instead to live a life ‘in contact with reality’, as Nozick put it. That is, to take part of experiences authentically of the world — reflecting a reality of greater consequence than a manufactured illusion. A choice that originates, at least in part, from a bias toward the status quo. This so-called status quo bias leads some people — if told to imagine their lives to date having been produced by an ‘experience machine’ — to choose not to detach from the machine.

However, researchers have found many people are reluctant to plug into the machine. This seems to be due to several factors. Factors beyond individuals finding the thought of plugging in ‘too scary, icky, or alien’, as philosopher Ben Bramble interestingly characterised the prospect. And beyond such prosaic grounds as apprehension of something askew happening. For example, either the complex technology could malfunction, or the technicians overseeing the process might be sloppy one day, or there might be malign human intrusion (along the lines of the ‘fundamentalist zealots’ that Bramble invented) — any of which might cause a person’s experience in the machine to go terribly awry.

A philosophical reason to refuse being plugged in is that we prefer to do things, not just experience things, the former bringing deeper meaning to life than simply figuring out how to maximise pleasure and minimise pain. So, for example, it’s more rewarding to objectively (actually) write great plays, visit a foreign land, win chess championships, make new friends, compose orchestral music, terraform Mars, love one’s children, have a conversation with Plato, or invent new thought experiments than only subjectively think we did. An intuitive preference we have for tangible achievements and experiences over machine-made, simulated sensations.

Another factor in choosing not to plug into the machine may be that we’re apprehensive about the resulting loss of autonomy and free will in sorting choices, making decisions, taking action, and being accountable for consequences. People don’t want to be deprived of the perceived dignity that comes from self-regulation and intentional behaviour. That is, we wouldn’t want to defer to the Experience Machine to make determinations about life on our behalf, such as how to excel at or enjoy activities, without giving us the opportunity to intervene, to veto, to remold as we see fit. An autonomy or agency we prefer, even if all that might cause far more aggrievement than the supposed bliss provided by Nozick’s thought experiment.

Further in that vein, sensations are often understood, appreciated, and made real by their opposites. That is to say, in order for us to feel pleasure, arguably we must also experience its contrast: some manner of disappointment, obstacles, sorrow, and pain. So, to feel the pride of hearing our original orchestral composition played to an audience’s adulation, our journey getting there might have been dotted by occasional stumbles, even occasionally critical reviews. Besides, it’s conceivable that a menu only of successes and pleasure might grow tedious, and less and less satisfying with time, in face of its interminable predictability.

Human connections deeply matter, too, of course, all part of a life that conforms with Nozick’s notion of maintaining ‘contact with reality’. Yes, as long as we’re plugged in we’d be unaware of the inauthenticity of relationships with the family members and friends simulated by the machine. But the nontrivial fact is that family and friends in the real world — outside the machine — would remain unreachable.

Because we’d be blithely unaware of the sadness of not being reachable by family and friends for as long as we’re hooked up to the electrodes, we would have no reason to be concerned once embedded in the experience machine. Yet real family and friends, in the outside world, whom we care about may indeed grieve. The anticipation of such grief by loved ones in the real world may well lead most of us to reject lowering ourselves into the machine for a life of counterfeit relationships.

In light of these sundry factors, especially the loss of relationships outside of the device, Nozick concludes that the pursuit of hedonic pleasure in the form of simulations — the constructs of the mind that the Experience Machine would provide in place of objective reality – makes plugging into the machine a lot less attractive. Indeed, he says, it begins to look more like ‘a kind of suicide’.

14 March 2022

A Scientific Method of Holism

Holistic thinking is much to be desired. It makes us more rounded, more balanced, and more skilled in every sphere, whether practical, structural, moral, intellectual, physical, emotional, or spiritual.

Yet how may we attain it?

Is holism something that we may merely hope for, merely aspire to, as we make our own best way forward—or is there a scientific method of pursuing it? Happily, yes, there is a scientific method of holism, although it is little known.

The video clip above, of 11 March 2022, gives us a classic example of the method—or rather, of one of its aspects. Here, CNN interviewer Alex Marquardt asks (so called) oligarch Mikhail Khodorkovsky, ‘Do they have any influence, these oligarchs ... any pressure, any sway, that they can put on President Putin?’

Khodorkovsky replies, ‘They cannot influence him. However, he can use them as a tool of influence, to influence the West.’

Notice, firstly, that the interviewer’s question is limited to the possibility of oligarchs influencing President Putin. It does not appear to cross his mind that influence could have another direction.

Khodorkovsky therefore brings a directional opposite into play, to reveal something that the interviewer does not see. In this way, he greatly expands our undertstanding of the situation. Khodorkovsky could have measured his answer to the question—'Do they have any influence ... on President Putin?’—but he did not. Instantly, he thought more holistically.

In linguistics, a directional opposite is one of several types of opposite—sometimes called oppositions. Directional opposites represent opposite directions on an axis: I influence you, you influence me; this goes up, that goes down, and so on.

Two more familiar types of opposite are the antonym, which represents opposite extremes on a scale: that house is big, this house is small; we could seek war, we could seek peace. Then, there are heteronyms,* which represent alternatives within a given domain: Monday comes before Tuesday, which comes before Wednesday; we could travel by car, by boat, or by plane.

How then may we apply these types of opposite?

In any given situation, we may examine the words which we use to describe it. Then we may search for their directional opposites, antonyms, heteronyms**—to consider how these may complement or expand the thoughts which we have thought so far.

As observed in the video clip above, this is not merely ‘semantics’. It genuinely opens up other possibilities to our thinking, and leads us into a greater holism. This applies in a multitude of fields, whether, for example, researching a subject, crafting an object, pursuing a goal, or solving a personal dilemma.

* Heteronyms may be variously defined. The linguist Sebastian Löbner defines them as 'members of a set'. This is how I define them here.

** One may add, in particular, complementaries and converses.

07 March 2022

Picture Post #72 Steerage

‘The scene fascinated me: A round straw hat; the funnel leaning left, the stairway leaning right; the white drawbridge, its railings made of chain; white suspenders crossed on the back of a man below; circular iron machinery; a mast that cut into the sky, completing a triangle. I stood spellbound for a while. I saw shapes related to one another -- a picture of shapes, and underlying it, a new vision that held me...’

One of the most influential photographers of the 20th Century, Stieglitz argued that photography should be taken as seriously as an art form. His work helped to change the way many viewed photography while his galleries in New York featured many of the best photographers of the day.

This image, simply called ‘The Steerage’, not only encapsulates what he called ‘straight’ photography – offering a truthful take on the world – but also tries to give us a more complex understanding by conveying abstraction through shapes and their relationships to one another.

27 February 2022

Suffering and Assumptions about God

by John Hansen

|

| 1825. William Blake. Job Plate 11. |

One of the perennial questions in philosophy is that, if God is both all-powerful and all-loving—assuming, that is, that he* exists—how is it that he permits suffering and evil in this world? We may imagine, for example, the gruesome suffering of a child, or a natural catastrophe.

One of the most influential thinkers in this area was John Hick (1922-2012), an American philosopher of religion and a theologian. Hick was an unconventional thinker, to the extent that he was twice the subject of heresy hearings. Yet his arguments on human suffering set the agenda. Hick held, to put it simply, that there is no evil in our suffering, but suffering improves our souls. That is, suffering is ultimately good, and merely appears to be evil.

There are multiple biblical references that suggest Hick's thesis: not only does God permit human suffering, but he actually endorses it. The story of Job is the prototype where God actually allows Satan to harm the righteous person (Job) in order to make him more ‘god-like’.

Since Hick, there have been new arguments, which Hick himself could hardly have imagined. Lately, there has been great interest in B.C. Johnson, who is not a theologian—yet through the strength of his arguments, has gained a large following. Johnson holds, to put it too simply, that everywhere, awful ‘accidents’ happen without the interventions of an all-powerful God. Therefore God is evil, or part good and part evil.

However, we find many unexamined assumptions, in both Hick and Johnson. We here examine some of them.

1. Both Hick and Johnson assume that God is personal—essentially, human in nature. Yet nowhere do they discuss this assumption. Is God human? If so, how? Thus they assign to God human codes of conduct. As a result, their discussion about God is essentially one about human morality. The question arises: do we justifiably refer to human morality, expecting God to conform with what is ‘human’?

2. Johnson assumes that God 'has refused to help' us in our sufferings -- and thus he must be evil. The assumption is that God would help us, unasked. One could conceive of an all-powerful, all-loving God who would not intervene in human affairs unless he was petitioned to do so—through a person with the requisite ‘faith’ to make the request. It would not be illogical to assume that God should be asked, by someone who believed that it was worth asking.

3. Almost every example that Johnson uses to question the goodness of God is found in his use of ‘accidents’. The assumption here, however, is that God has power over that realm. Even an all-powerful God could, presumably, leave some things alone. One could posit that a good God would not want to disturb the accidents of nature, because such intervention could disturb the flow of our environmental process. Perhaps he chooses rather to be all-powerful in the spiritual realm.

4. Hick, on the other hand, asks whether accidents can ever be called evil. In that case, can one assume a motive? A classic example is a hornet’s sting. Was there evil intent? Hick equates moral evil with human wickedness, and non-moral evil as equivalent to human pain and suffering from other sources. The distinction is important because Hick suggests that, in the case of human wickedness, we as free agents are in control. God himself may have no evil intent.

5. Johnson questions the theist’s ‘retreat to faith’ to explain God’s goodness. Such faith, he holds, cannot be justified in a wider context. When one casts an eye over history, God’s record is not good. Yet may it not be a category mistake? Faith is a matter of spiritual ascertainment and may make little sense when applied to human rules or philosophical analysis. Faith may not need to be ‘justifiable’ in terms of our own notions of right and wrong.

6. Skeptics may assume that God should have created the world as a hedonistic paradise devoid of human suffering. Suffering and evil may themselves be interpreted as good. God may have created the world to include pain and suffering. The necessity of such suffering, in turn, would bring about God-like characteristics that are necessary. According to Hick, if God were to eradicate all human suffering, we would drift through life aimlessly as if in a dream.

7. A final assumption of the skeptic is that God knows nothing of suffering. Yet an omnipotent, good God himself may have suffered throughout history, just as much as humanity has done, if not more. Such an all-powerful God may believe that it is necessary for human beings to suffer in a similar way as he has done, in order to become more like him, in a different state of existence.

Whether or not one agrees with Hick’s conclusions, it is submitted that his arguments are more plausible than Johnson’s, in that they do not attempt to analyse an unanalysable faith. We may have no better language to talk about it than this.

* I follow Rabbi Aryeh Kaplan: ‘We refer to G-d using masculine terms simply for convenience's sake ...’

20 February 2022

Rethinking Energy as Moral Energy

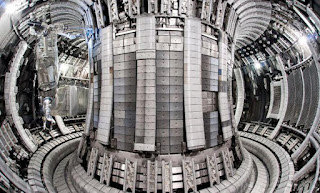

|

| Nuclear fusion is again being offered as the solution to human energy needs. |

By Andrew Porter

On February 9, 2022, scientists working in an English village near Oxford announced that in December they were able to generate a few successful sustained seconds of nuclear fusion. An article for CNN by Danya Gainor and Angela Dewan declared that:

‘A giant donut-shaped machine just proved a near-limitless clean power source is possible’.The energy machine generated a record-breaking 59 megajoules for over five seconds. Heat ten times hotter than the center of the sun – as high as 150 million degrees Celsius. The process generates tremendous pressure. And then the magnets overheat.

This kind of development is almost universally hailed as an advance. It promises to one day meet energy demand that burgeons with increasing human population. Such energy may be able to utilize the deuterium and tritium in seawater to power houses and businesses – as the crisis of climate change applies heat and pressure of its own. But I want to suggest that finding a source for more energy should not be the world's focus, as reasonable as it sounds. That there may instead be better uses of energy possible for us.

One person may argue: ‘We live in a contemporary world with vast energy needs and we have to develop the technology to address problems’. This the voice of what is considered ‘realism’. But as Shira Ovide, a New York Times writer, says: ‘Climate change and other deep-seated problems are hard to confront, and it’s tempting to distract ourselves by hoping that technology can save the day… But technology isn’t magic and there are no quick fixes.’ Another person may contend that the kind of worldview that got us into this mess will not get us out. So it is worth asking what really is beneficial, not just short term but long term.

The ‘glitzy’ new advance in nuclar fusion seems, on the surface, to be of benefit. But our high-energy-use ways are unsustainable and damaging. It seems to me that the task for communities, nations, and humankind in general is, in this time of planetary pressure and the retooling of mindsets, to generate human ecology, so we might live within natural parameters and carrying capacities. This is the opposite of finding new ‘resources to exploit’ for untenable practices and assumptions.

Now you may ask, ‘Well, if it's cheap and renewable, why not embrace nuclear fusion?’ Behind this question is the hope that there will be no reckoning, that we will not have to mend our planet-damaging ways. But our energy needs to be mental, cultural, and philosophical. Peter Sutoris, anthropologist of development and the environment, and author of Educating for the Anthropocene, says:

‘We must face up to the harsh reality that for all its achievements, our civilisation is deeply flawed. It will take a reimagination of who we are to truly solve this crisis’.

Who can seriously argue that it is not time to craft a new human way of being on Earth? This ‘new human way’ I imagine as much simpler, low-tech, and integral with other life forms.

The likelihood is very strong that people at all levels will reject a shift away from grabbing more energy. Rising sea levels will submerge huge swathes of coastline because of the industrialised world's aversion to ecological ways of life. But thorough-going, Earth-friendly ideals, were they chosen, could be the crucial spur to enact positive change in societies and provide an aim for what's accepted, embraced, and funded. The ‘tokamak’ fusion machine near Oxford cannot provide the needed energy. What is most pertinent for our time is inferably moral energy – along with philosophical clarity – to steer us all away from human excesses and towards an attunement to natural limits. This is to suggest that the fusion that’s optimally generated is internal.

That’s the real enterprise – the energy use – worthy of our savvy.

13 February 2022

The Ethics of ‘Opt-out, Presumed-Consent’ Organ Donation

By Keith Tidman

According to current data, in the United States alone, some 107,000 people are now awaiting a life-saving organ transplant. Many times that number are of course in similar dire need worldwide, a situation found exasperating by many physicians, organ-donation activists, and patients and their families.

The trouble is that there’s a yawning lag between the number of organs donated in the United States and the number needed. The result is that by some estimates 22 Americans die every day, totaling 8,000 a year, while they desperately wait for a transplant that isn’t available in time.

It’s both a national and global challenge to balance the parallel exigencies — medical, social, and ethical — of recycling cadaveric kidneys, lungs, livers, pancreas, hearts, and other tissues in order to extend the lives of those with poorly functioning organs of their own, and more calamitously with end-stage organ failure.

The situation is made worse by the following discrepancy: Whereas 95% of adult Americans say they support organ donation upon a donor’s brain death, only slightly more than half actually register. Deeds don’t match bold proclamations. The resulting bottom line is there were only 14,000 donors in 2021, well shy of need. Again, the same worldwide, but in many cases much worse and fraught.

Yet, at the same time, there’s the following encouraging ratio, which points to the benefits of deceased-donor programs and should spur action: The organs garnered from one donor can astoundingly save eight lives.

Might the remedy for the gaping lag between need and availability therefore be to switch the model of cadaveric organ donation: from the opt-in, or expressed-consent, program to an op-out, or presumed-consent, program? There are several ways that America, and other opt-in countries, would benefit from this shift in organ-donation models.

One is that among the many nations having experienced an opt-out program — from Spain, Belgium, Japan, and Croatia to Columbia, Norway, Chile, and Singapore, among many others — presumed-consent rates in some cases reach over 90%.

Here’s just one instance of such extraordinary success: Whereas Germany, with an opt-in system, hovers around a low 12% consent rate, its neighbour, Austria, with an opt-out system, boasts a 99% presumed-consent rate.

An alternative approach that, however, raises new ethical issues might be for more countries to incentivise their citizens to register as organ donors, and stay on national registers for a minimum number of years. The incentive would be to move them up the queue as organ recipients, should they need a transplant in the future. Registered donors might spike, while patients’ needs have a better hope of getting met.

Some ethical, medical, and legal circles acknowledge there’s conceivably a strong version and a weak version of presumed-consent (opt-out) organ recovery. The strong variant excludes the donor’s family from hampering the donation process. The weak variant of presumed consent, meanwhile, requires the go-ahead of the donor’s family, if the family can be found, before organs may be recovered. How well all that works in practice is unclear.

Meanwhile, whereas people might believe that donating cadaveric organs to ailing people is an ethically admissible act, indeed of great benefit to communities, they might well draw the ethical line at donation somehow being mandated by society.

Another issue raised by some bioethicists concerns whether the organs of a brain-dead person are kept artificially functional, this to maximize the odds of successful recovery and donation. Doing so affects both the expressed-consent and presumed-consent models of donation, sometimes requiring to keep organs animate.

An ethical benefit of the opt-out model is that it still honours the principles of agency and self-determination, as core values, while protecting the rights of objectors to donation. That is, if some people wish to decline donating their cadaveric organs — perhaps because of religion (albeit many religions approve organ donation), personal philosophy, notions of what makes a ‘whole person’ even in death, or simple qualms — those individuals can freely choose not to donate organs.

In line with these principles, it’s imperative that each person be allowed to retain autonomy over his or her organs and body, balancing perceived goals around saving lives and the actions required to reach those goals. Decision-making authority continues to rest primarily in the hands of the individual.

From a utilitarian standpoint, an opt-out organ-donation program entailing presumed consent provides society with the greatest good for the greatest number of people — the classic utilitarian formula. Yet, the formula needs to account for the expectation that some people, who never wished for their cadeveric organs to be donated, simply never got around to opting out — which may be the entry point for family intervention in the case of the weak version of presumed consent.

From a consequentialist standpoint, there are many patients, with lives hanging by a precariously thinning thread, whose wellbeing is greatly improved (life giving) by repurposing valuable, essential organs through cadaveric organ transplantation. This consequentialist calculation points to the care needed to reassure the community that every medical effort is of course still made to save prospective, dying donors.

From the standpoint of altruism, the calculus is generally the same whether a person, in an opt-in country, in fact does register to donate their organs; or whether a person, in an opt-out country, chooses to leave intact their status of presumed consent. In either scenario, informed permission — expressed or presumed — to recover organs is granted and many more lives saved.

For reasons such as those laid out here, in my assessment the balance of the life-saving medical, pragmatic (supply-side efficiency), and ethical imperatives means that countries like the United States ought to switch from the opt-in, expressed-consent standard of cadaveric organ donation to the opt-out, presumed-consent standard.

06 February 2022

In Praise of Monarchy

This drive towards predictability and control included political systems. Hereditary monarchs, who were often fickle, volatile, unpredictable—and too often, simply dangerous—were increasingly reined in or replaced by more regular and predictable dispensations. Republicanism in particular gained in favour, in the sense of ‘a scientific approach to politics and governance’.

I pause this post now to turn my attention to you, the reader. Without saying as much, you and I have—if indeed it is agreed—developed the argument that the character of hereditary monarchy has been shaped by the era and intellectual climate in which it existed. Therefore, our attitude towards monarchy, and the desirability of monarchy itself, has to do with historical eras—most immediately, pre-modernity, modernity, and postmodernity.

- That human fate is bound up always with the uncertainty and ambiguity of personality and personal destiny. The ‘humanity’ which we find in systems, both good and bad, will not be worked out of them. Hereditary monarchy reminds us that our fate is bound up with personal factors, and our own designs and expectations continually confounded.

- Hereditary monarchy reminds us that government itself cannot ultimately be reduced to reason and rules, and that systematic control is elusive. Monarchy, in an important sense, now represents accident and freedom, rather than the regimentation and subjection it once did.

- We are reminded, through hereditary monarchy, that government is not a mere administrative function, but can only be properly viewed where we include personal meaning. It is not all of it about rational, scientific, or even efficient control, but often it comes down to the mystery of semiotic codes: a smile, a gesture, a cup of tea, or a set of brooches.

- Hereditary monarchy, contrary to what once was the case, withers metanarratives and ideologies, which have been so destructive to humanity in the past. It shows us that there is no novum ordo, no social optimism, no Omega Point. Instead, we have people, with limited lifetimes, and limited capabilities.

- With individuals being the focus of hereditary monarchy, we are reminded, in fact on a daily basis, that monarchies are fallible—perhaps moreso than we may recognise it in the entirety of a republican order. Rather than representing autocracy, as once was the case, hereditary monarchy reminds us of the necessity of checks and balances.

30 January 2022

The Virus Stats that Cost Everyone a Lot

So, travel with me back nearly two years to the origins, and take a second look at some key metrics that have been tossed about ever since. One problematic measure has been the “Case Fatality Rate”. This was officially put by the United Nations at just under 1%, making Covid a very deadly virus.

The bit we can agree on is the definition. The CFR is the number of deaths from Covid divided by the number of “confirmed cases”.

The problem is that deciding who actually died “from Covid” is very murky. A typical report is that 95% of people dying from Covid have other co-morbidities. This means that they may actually have died from these rather than from Covid. The issue is exacerbated when you see that the typical age of someone dying “from Covid” is pretty much the age at which anyone dies.

So the numerator part of this crucial figure is HIGHLY debatable - and the denominator part, the number of cases is too. For starters, one problem is that what you, me and Joe Public understand as “a confirmed case” is someone who has symptoms and goes to hospital and is tested and found to have the virus. That would all make sense. But in fact, a case is simply someone who has the virus. And again, it is agreed that the great majority of people who encounter the virus never have any symptoms. These people are often not counted. This is why the number of cases a country has depends essentially on how much testing the government chooses to do.

To make matters worse, it depends on the criteria used for the test. The benchmark test, the so called PCR (polymerase chain reaction ) test, considered “the gold standard” for detecting Covid. The test amplifies genetic matter from the virus in cycles; the more cycles used, the greater the amount of virus, or viral load, found in the sample. Crucial to the test, then, is how many cycles are used -and that, perhaps surprisingly, is not a medical decision but a political one. In Europe, for example, The European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control does not recommend a specific maximum amplification cycle threshold for PCR tests. However, it does recommend that if the values are high, e.g. > 35, “repeated testing should be considered”. In other words, it recognises the results are unsafe.

Yet that decision on the number of cycles is not even communicated when a “positive test” is returned. As Angela Rasmussen, a virologist at Columbia University in New York told the New York Times, “It’s just kind of mind-blowing to me that people are not recording the C.T. values from all these tests — that they’re just returning a positive or a negative.”

Ultimately, there is no standard cycle threshold value that is agreed upon internationally. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration currently gives laboratory manufacturers autonomy in determining how many cycles are needed to determine whether a sample is positive or negative.

How accurate the test is matters, because everyone admitted to hospital, for whatever reason - maybe they had a heart attack - is routinely tested for Covid. If they are considered positive, and later on die, they will be counted as a Covid fatality, as “dying within 21 days of a positive test”.

So that’s three rather big question-marks lurking in the Covid data. But the next one, I think, is worse. This statistic purports to show vaccines save people from the worst effects of the disease.

It’s the statistic that led the CDC in the US to say:

“COVID-19 vaccines are highly effective at preventing severe COVID-19 and death.”And you can read that in all the papers, in all the fact-checkers, and so you “might” think it must be true. However, statisticians at Queen Mary College in London, looked at the UK data (which is representative of other countries too) and concluded:

"Official mortality data for England suggest systematic miscategorisation of vaccine status and uncertain effectiveness of C19 vaccination”They noticed that the official statistics showed that, following vaccination, the UNVACCINATED died. The so’-called healthy vaccine' effect. A less cheery explanation was that vaccines might actually be killing people - but if the deaths occurred within 21 days, as most side-effects do - being classified as deaths of “unvaccinated”.

This is a possibility, and adverse effects databases like the European EudraVigilance database and US VAERs ones currently report alarmingly high numbers, in apparently compelling detail – however the miscategorisation does not need to mean that vaccines are killing a lot of elderly people. Rather, fragile people are prioritised for vaccination, and thus skew the figures. However, by grouping vulnerable people together statistically to be vaxed and then … calling this group the unvaccinated, the authorities have very conveniently created an apparently miraculous positive effect for vaccines. That it is not really there is indicated that the positive effect is not only for Covid but for ALL CAUSE mortality!

This is known. Yet far from accepting the statistics mislead, governments and drug companies surmise that the treatments may have unexpected general positive effects.

In reality, the statistical anomaly is large because in countries like the UK, the NHS Guidelines explicitly state that the most critically ill people are the ones who must be prioritised for vaccination in each age group.

Let me try to sum it all up in three sentences! Vaccine data shows most of the advantage from the jab in the first few months. Because Covid vaccination programs prioritise very ill people, a significant number of whom die in the following 21 days - not from the vax necessarily, just because they were, well, vulnerable. Whatever the reason, again under the official guidelines, these deaths are classed as "unvaccinated", creating the “bad news” for the unvax and the amazing, parallel, health boost for the vaxed.

So there you have it. Some examples of how duff statistics, not anything more secretive let alone worrying, created a Ten Trillion Dollar “pandemic” that never was.